GEORGE HULL was born on 13 Aug 1787 in Parish

of Iwerne, Dorset, England. He died on 23 Jun

1879 in “Royston Cottage”, Battery Point, Hobart,

Tasmania, Australia. He married Anna MUNRO,

daughter of Lieutenant Hugh MUNRO and Jane

DAVIS on 27 Aug 1815 in St Pancras Church,

Middlesex, England, UK. She was born on 09 Feb

1800 in St Marys, Isles of Scilly, Cornwall, England.

She died on 27 Jan 1877 in “Tolosa”, O’Brian’s

Bridge, Hobart, Tasmania, Australia.

George HULL and Anna MUNRO had the

following children:

1. GEORGINA ROSE HULL was born on 23 Aug

1816 in Westminster, London, England. She died

on 20 Jul 1886 in Hamilton, Victoria, Australia.

She married Philip George EMMETT on 17

Jan 1837 in Hobart, Tasmania, Australia. He

was born on 22 Oct 1810 in Parish of St. James

Westminster London England. He died on 15 Jul

1871 in Corop, Victoria, Australia.

2. HUGH MUNRO HULL was born on 19

Apr 1818 in Romney Terrace, Westminster,

London, England. He died on 03 Apr 1882 in

197 Macquarie St, Hobart, Tasmania, Australia.

He married (1) ANTOINETTE MARTHA

AITKEN, daughter of James AITKEN and

Jane SYNNOT on 31 Oct 1844 in ‘Glen Esk’

Launceston, Tasmania. She was born on 12

May 1825 in Hobart, Tasmania, Australia. She

died on 23 Jul 1852 in “Tolosa”, Glenorchy,

Hobart, Australia. He married (2) MARGARET

BASSETT TREMLETT, daughter of William

TREMLETT and Margaret AITKEN on 03 Jan

1854 in Campbell Town, Tasmania, Australia.

She was born on 05 Nov 1835 in “Glen Esk”,

Cleveland, Van Dieman’s Land, Australia. She

died on 02 Dec 1891 in ‘Dunstanville’ Hobart,

Tasmania, Australia.

3. FREDERICK GEORGE HULL was born on 19

Dec 1819 in Launceston, Van Dieman’s Land,

Australia. He died on 11 Apr 1876 in Buninyong,

Victoria, Australia. He married Sophia Louisa

TURRELL, daughter of Charles TURRELL

and Ann WALLACE on 14 Feb 1844 in New

Town, St Johns Church, Van Diemans Land.

She was born about 1816 in Verdun, Meuse,

Lorraine, France. She died on 03 Feb 1889 at

“Glen Lyndon”, Lyons Street, Ballarat, Victoria,

Australia,

4. ROBERT EDWARD HULL was born on 02 Jun

1821 in Hobart, Van Dieman’s Land, Australia.

He died on 18 Jul 1841 in Hobart, Van Dieman’s

Land, Australia.

5. HARRIET JANE HULL was born on 05 May

1823 in “Tolosa”, Glenorchy, Van Dieman’s Land,

Australia. She died on 10 Jan 1912 in “Royston

Cottage”, Battery Point, Hobart, Tasmania,

Australia. She married Frederick Arundel

DOWNING on 01 Jun 1844 in New Town, St

John’s Church, Van Dieman’s Land. He was

born on 16 Jan 1809. He died on 03 Jan 1895

at “Royston Cottage”, Colville Street, Battery

Point, Tasmania.

6. GEORGE THOMAS WILLIAM HULL was born on 08 Oct 1825 in Launceston, Van

Dieman’s Land, Australia. He died on 25

Mar 1914 in Clunes, Victoria, Australia. He

married Caroline Robart ROBERT, daughter

of John ROBERT and Elizabeth Ann Pritchard

PERKINS on 23 Dec 1857 in Amherst, Victoria,

Australia. She was born on 26 Aug 1839 in

Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. She died on 16

Jun 1905 in Dunach, Victoria, Australia.

7. TEMPLE PEARSON BARNES HULL was born

on 22 Aug 1827 in Launceston, Van Dieman’s

Land, Australia. He died on 11 Sep 1888 in

Ararat, Victoria, Australia.

8. HENRY JOCELYN HULL was born on 16

Jul 1829 in Launceston, Van Dieman’s Land,

Australia. He died on 03 Sep 1893 in “Glen

Lynden”, Glenorchy, Tasmania, Australia. He married Mary Jane WILKINSON, daughter of

John Norton WILKINSON and Sarah Anne

WARE on 22 Nov 1861 in Hobart, Tasmania,

Australia. She was born on 27 Dec 1836 in

Hobart, Tasmania, Australia. She died on 10

Dec 1920 in Glenorchy, Tasmania, Australia.

9. ANNA MUNRO HULL was born on 19 Jun

1831 in “Tolosa”, Glenorchy, Van Dieman’s

Land, Australia. She died on 05 Dec 1887 in

Campbelltown, Tasmania. She married Thomas

Henry POWER on 10 Aug 1850 in New Town,

AUSTRALIA, St John’s Church, Van Dieman’s

Land. He was born in 1828 in Ireland. He died

on 19 Apr 1901 in Campbelltown, Tasmania,

Australia.

10. JAMES DOUGLAS HULL was born on 21 Jul

1833 in “Tolosa”, Glenorchy, Van Dieman’s Land,

Australia. He died on 05 Nov 1881 in “Glen

Lynden”, Glenorchy, Tasmania, Australia. He

married Eliza Ann CLOTHIER, daughter of

John Edward CLOTHIER and Anne ALDEN

on 25 Oct 1855 in Holy Trinity Church, Hobart,

Van Dieman’s Land. She was born on 13 Sep 1835

in Hobart, Tasmania, Australia. She died on 25

Apr 1873 in New Norfolk, Tasmania, Australia.

11. JOHN FRANKLIN OCTAVIUS HULL was

born on 08 Apr 1836 in “Tolosa”, Glenorchy,

Van Dieman’s Land, Australia. He died on 17

Mar 1874 in Glenorchy, Tasmania, Australia.

He married MARY ANN LESTER. She died in

1874.

12. ALFRED ARTHUR HULL was born on 16

Feb 1839 in “Tolosa”, Glenorchy, Van Dieman’s

Land, Australia. He died on 18 Nov 1890

in Robert Street, Toowong, Queensland,

Australia. He married Mary Anna (Minnie)

BARNS, daughter of William BARNS and

Sarah BROWN on 27 Jun 1865 in Maryborough,

Queensland, Australia. She was born on 25 Apr

1849 in Dudley, Staffordshire, England. She died

on 12 Dec 1884 in Sandy Bay, Hobart, Tasmania,

Australia.

13. MARY EMILY (POLLY) HULL was born

on 25 Jun 1841 in Hobart, Van Dieman’s

Land, Australia. She died on 13 Jun 1928 in

Tambourine Mountain, Queensland. She

married William Montgomerie Davenport

DAVIDSON, son of Crisp Molyneux (Or

Molineux) MONTGOMERIE and Isabella

Davenport DAVIDSON on 01 Feb 1860 in Hobart, Tasmania, Australia. He was born on

20 Jun 1830 in Richmond, Surrey, England. He

died on 07 May 1909 in Brisbane, Queensland,

Australia.

written by his eldest son, Hugh Munro Hull.

My grandfather (George Hull) was a man of commanding appearance 6 foot 2 inches high & was a member of the Surrey Royal Grenadiers. He was the youngest son & having received a good education was placed in a position with a Lawyer in Micham Surry, later on, on the influence of Sir Thomas Wood Bart, he was secured a position in the Commissariat office.

In 1810 he proceeded to Spain & Portugal & saw service there under the Duke of Wellington in 1814 he was promoted to Deputy Assistant Commissary General & at the close of the war in 1815 he returned to England & married my mother, Anna Munro daughter of Lieutenant Hugh Munro then a Lieutenant of the Royal Veterans Battalion & stationed at the Scilly Islands, he was previously a Captain in the Coldstream Guards but was practically blinded by a cannon blast in the Walcheren Expedition.

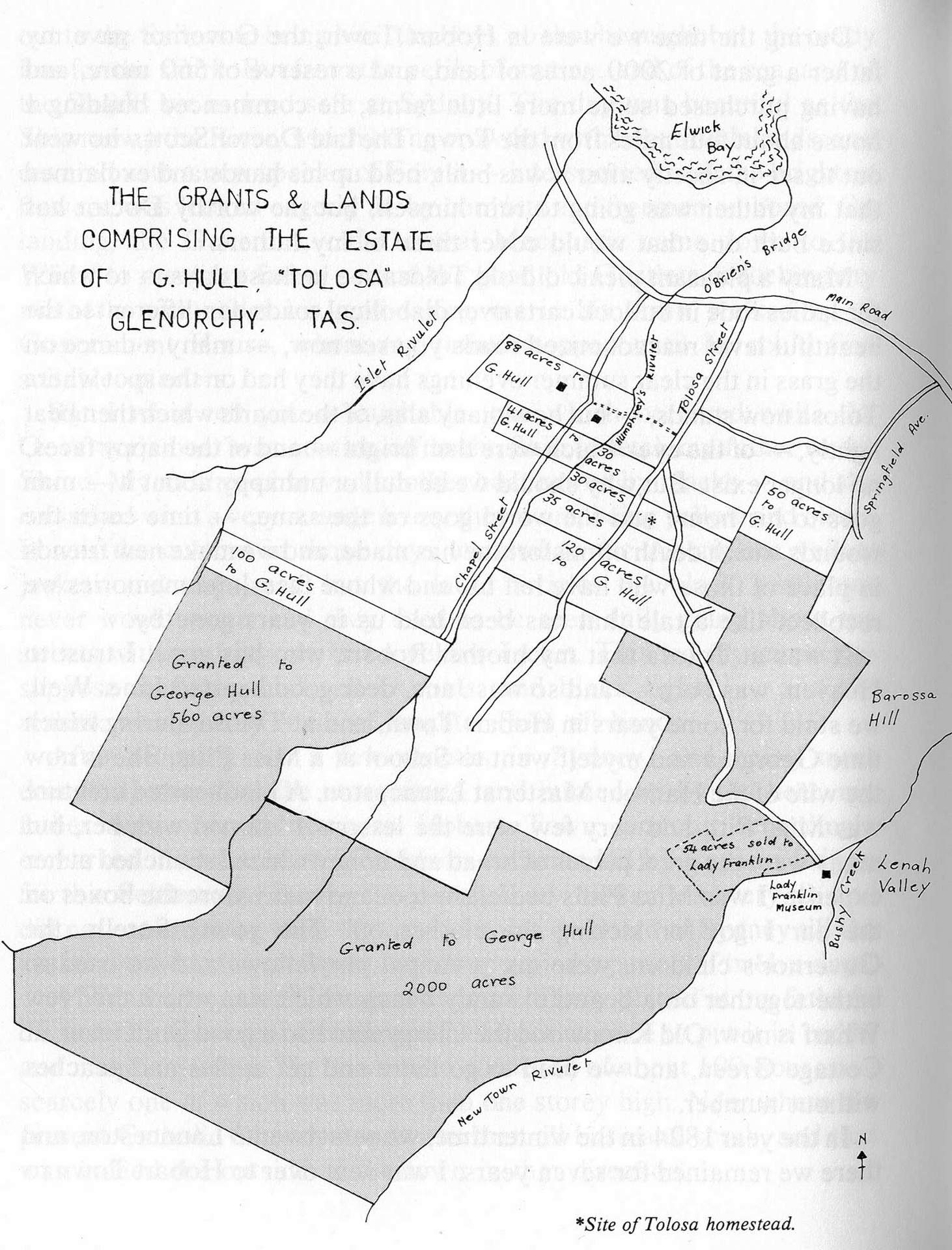

Anna Munro was 15 years of age when my Father presented a letter of introduction to Govt. Macquarie, from Earl Bathurst v Lord Goulburn, he remained some months as a guest of Govt. Macquarie & then as he stated being eaten up by flies in the day, & mosquitos by night & being most dreadfully burnt up by the heat he requested a transfer to Van Diemen’s Land & this being granted he and his family left Sydney in the Brig "Admiral Cockburn" for Hobart, the voyage took 12 days & bad weather all the time. Arriving in Hobart he took up his duties as Commissariat Officer & remained there until 1823, he was then transferred to Launceston with the position as Kings Bonded Warehouse Keeper & Treasury Official, there was seldom sufficient cash or currency to pay his salary so he had to take the balance out in Rum, the result was many convivial parties at his house. In 1831 he retired, (on account of deafness) on half pay & took up farming at Glenorchy some little way out of Hobart, here he had built his home & called it ‘Tolosa’ while stationed in Hobart on the 2560 acres of land which had been granted to him

by Govt. Sorell. He died in 1879 at the age of 93, his

wife predeceased him aged 77, he left 10 children

living out of 13 & I was the eldest son.

PENINSULAR SERVICE

George Hull, born 22-8-1786, entered the army as a

Treasury Clerk in the Commissariat Department

in 1810, aged 24, through the interest of Sir Marcus

Wood, Bart. M.P., at a time when Napoleon was

rampant through Europe. He served under the Duke

of Wellington at the Battle of Fuentos d’Onore on

May 5th 1811, and later at the Battles of Albuera,

Rodrigo, Salamanca, Vittoria, Orthes, Toulouse, and

remained at the seat of war until its termination at

the Battle

of Waterloo in June 1815.

In January 1814 he was promoted to Deputy

Assistant Commissary General to the Army, having

received a commission from Lord Wellington. Of

the various hairbreadth escapes and troubles he

had to go through, he would often give his sons

a most graphic account to their great delight.

Unfortunately, through being so close to the scene

of action, he suffered great inner-ear damage, so

that he was practically deaf by the age of 45, and was

troubled by awful dizziness in his old age.

At the close of the war in 1815 Hull returned to

England and was employed for nearly three years in

Somerset House in the Commissariat of Accounts,

as auditor of accounts of the Penninsular War and

the recent war in America. As can be imagined

there was no great orderliness in the accounts kept

at the scene of battle and it was his job to put chaos

into order. Some officers had over-drawn their pay

accounts, some were due for pensions, and the War

Office was wanting to know what the final cost would

be.

When this task was completed and his duties ended

he was given the option of retiring on half-pay or

going on Foreign Service. He was given the choice of

service in Canada or New South Wales, and he chose

the latter.

Soon after his return to London, on 27th August

1815, he had married Anna Munro, the daughter

of Lieutenant Hugh Munro of the Royal Veteran

Battalion stationed at the Tower of London. George

had just turned 29 and Anna was barely 15.

On 23-8-1816 their first child, Georgina Rose, was

born; (Rose being the family name of Anna’s

mother). Nineteen months later on 19th March

1818, at Romney Terrace, Westminster, a little son

Hugh Munro Hull was born, and a few weeks after

his birth the family was prepared to take up their

position in the antipodes.

THE JOURNEY

The family packed all their belongings and took

possession of their small cabin on board the

“TYNE”, a convict ship which first sailed for Cork, in

Ireland, to take on 350 convicts destined for N.S.W.

Anna was only 18 years old and had scarcely ever

been out of London, and the beautiful Irish scenery

left an indelible impression on her, but the trip was

far from pleasant. With a two year old daughter and

a three week old baby, such confined quarters and a

journey that took seven months, Anna proved she

was a worthy wife for a soldier and pioneer.

At no port would the gruff old Captain touch for

supplies. A mutiny broke out amongst the convicts,

and when the plan was discovered by the treachery

of one of the conspirators, it was found that the

fellows had determined to murder all on board who

were not in the same condition as themselves, and

to put the Hull family on shore at the first land they

met. To this act of kindness they were moved by some

civilities, which had been offered by Hull to some of

the convicts who were, in Hull’s opinion, the best behaved

men on board.

Among the sailors the two little children were great

favorites and it was pleasing to see the great “sea

monsters” all striving to get the baby to nurse. As for

the Captain, whenever there was a shark alongside,

he, knowing that Anna was very nervous, used to

callout to the sailors to bring the baby so that he

might bait the ready line for the shark.

But from the perils of mutiny, and the sea, and of

the sharks, they all survived and Sydney was most

eagerly looked for by both convicts and freemen

alike.

The “TYNE” arrived at Sydney on January 4th 1819,

and Governor Macquarie went down to the wharf

to meet George Hull and took the family back to his

home until quarters were found for them.

Anna used to tell a joke against herself, about

an event that happened that first day. While the

Governor’s boat was coming over to the ship to

fetch the family ashore, Anna observed another

boat rowed by aborigines and she remarked what

a strange livery they wore, being yellow and black.

It was the custom in those days to issue to the

aborigines yellow jackets and trousers, but the latter

article the black gentlemen never would wear, and

they could be seen daily going about the streets with

nothing on but yellow jackets. This led Anna to

suppose that they had yellow coats and black tights,

and her remarks were met by roars of laughter by all

hands.

There were only 30,000 people in the whole colony at

this time, a greater proportion of them emancipists

who had their own cultivated land and own stock,

but due to Governor Macquarie’s building policy,

and his employment of Greenway, Sydney Town had

some beautiful and substantial public buildings,

and was taking on the appearance of a permanent

settlement. The road had been built across the Blue

Mountains only 4 years previous and the explorers

and pioneers were pushing westwards searching for

the inland sea.

A second settlement had been established at

Parramatta, 15 miles west of Sydney, which has

easy access by water and good pasturage, and was

so prosperous that it nearly threatened to overtake

Sydney. A large convict population with all

necessary buildings and offices was well established

there by 1819.

PARRAMATTA

A few days after Hull disembarked the new Deputy

Assistant Commissary

Frederick Drennan arrived on the ship “GLOBE”,

and was immediately put in charge of the

Commissariat Department for the whole colony

of N.S.W., which also incorporated Van Diemen’s

Land. He set about re-organising the system; he put

George Hull in charge of the store at Parramatta and

allowed him a free hand.

Hull commenced duty on January 25th and early in

March Drennan wrote a glowing report praising his

efforts.

Drennan told Governor Macquarie that the use of

store receipts in the colony was not in accordance

with treasury instructions; Macquarie was

unconvinced, but agreed to proposals to change the

system, store receipts were no longer to be regarded

as cash vouchers or as saleable and transferable, and

all payments were to be made in silver coin or in

Drennan’s own notes drawn on the Treasury.

Drennan’s relations with the Governor quickly

deteriorated and he offered so many criticisms of

Macquarie’s rule that by March 24th Macquarie

sent a lengthy criticism of Drennan’s conduct to the

Treasury in London.

In August Hull was offered a transfer to Hobart

which he was pleased to accept, as the climate was

more to his liking. He had complained in N.S.W. of

being burnt by the heat and dreadfully bitten by

mosquitoes and was not looking forward to a second

summer.

The Commissariat in V.D.L. had been run by

Thomas Archer for several years but his commission

had never been officiated and it was felt that the

growth of Hobart warranted a commissioned officer,

Drennan arranged passage for the family on the

“ADMIRAL COCKBURN”, commanded by Captain

Briggs, and after a voyage of 12 days the ship arrived

at Hobart Town on September 18th 1819. Poor

Anna was ill the whole voyage and could not eat a

thing, and was most thankful to put her feet on land

again.

HOBART TOWN 1819- 1823

George Hull and his family arrived at Hobart Town

three years after Lieutenant-Governor Sorell had

taken command of the colony. Sorell immediately

arranged for a weatherboard cottage, which stood

where the museum now stands, to be placed at Hull’s

disposal. Hull began at once to put it in order and

make a garden; between the Museum and the Town

Hall, in Argyle Street, was his potato patch and for

many years two large gum-trees stood at the gate in

Macquarie

Street, which he had planted on the day his son

Frederick George was born, December 28th 1819.

He had strolled up the bush to dig the little saplings

up, to where the Catholic Church was later built

all beyond that being thick scrub of tea-trees and

prickly mimosa.

The old house was later pulled down and made into

firewood, and according to Hugh its replacement

was not much better.

On September 25th 1819 George Hull officially

took over the running of the Commissariat and

all accounts, though still subsidiary to Drennan in

Sydney.

In 1819 Hobart Town consisted of about 100 houses,

scarcely one of which was more than one story high;

there were perhaps 15-20 dwellings worthy of the

name house. But there were a number of fine solid

government buildings; the new Barrack building,

the new gaol, the Garrison Church, the Commissary

store, the Guard House, and the Church of St.

David.

Immigration of free settlers was increasing with

the promises of free grants of land, the loan of

stock, and seeds, and abundant and cheap labour

(convicts). The plough had taken place of the hoe

and grain was exported to Sydney; but only two

farmers in the whole colony had fences protecting

their land.

Government House was just along Macquarie Street

from Hull’s first home, where lower Elizabeth Street

now is, between the present Town Hall and Franklin

Square. It was built of bricks made in the settlement

but was so poorly constructed that Sorell would not

move in until repairs had been carried out, and in

1824 Governor Arthur complained that it was totally

unfit for occupation. Directly opposite the end of

Elizabeth Street were the white wooden gate and the

main guardhouse of the Governor’s house. Sentries

at the gate stood stiffly in the red coats and shako

hats topped with a white woolen ball. A white paling

fence enclosed the garden and the area known as

the Government Paddock, which usually contained

a few Kangaroos and Tasmanian emus; this is now

Franklin Square.

The Church of England was the established

church in Tasmania for many years, and grew with

government support and finance. Many people

attended the services because it was the correct

thing to do – fashionable - rather than a matter of

conviction, but George Hull’s boyhood upbringing

as a Baptist had given him solid foundations and

strict morals. A rather scarce commodity in those

days.

The main church in Hobart when the family arrived

was St. David’s, which was built on the same block of

land as the present Cathedral. The foundation stone

of the first St. David’s was laid Feb. 19th 1817 and the

first service was held in this building on Christmas

Day 1819, although it was still without windows.

Little Frederick was baptised here on January 21st

1820, and must be among the first few babies to have

this honour.

In I820 Commissioner Bigge reported, “The new

church at Hobart Town is respectable in appearance,

but the workmanship, especially the building of the

walls, is defective. It is estimated to contain 1,000

persons. The assistance of another clergyman will

be desirable, on account of the increasing age and

infirmity of the present chaplain”. (Dr. Knopwood).

In 1822 a report in Sydney Gazette read, “In Hobart

Town is a Church which for beauty and convenience

cannot be excelled by any in the Australian

Hemisphere; and which, moreover, we are credibly

instructed to say, is now better attended than in days

of yore.”

The soldiers sat in the galleries on three sides of the

church, whilst on the central floor the “tall mellowed

cedar pews with lockable doors, denied glimpses of

elegance to the prisoners who crowded the body of

the nave. Knopwood preached his last sermon in it

on April 1823 before he retired, as his replacement

Dr. Bedford had arrived in January.

From the time of his arrival in Hobart, until he was

superseded on 12-5-1821, George Hull was in charge

of the Commissariat Department of Van Diemen’s

Land. He contracted for supplies of wheat and

meat from the settlers, he issued Store Receipts,

and he was in charge of the government herds. His

predecessor, Thomas Archer, acted as his assistant at

Port Dalrymple with Thomas Walker.

The state of the Commissariat in Hobart was far less

organised than in Sydney. Every Commissary officer

before 1819 was known to have fiddled the books, but

Hull was a man of Righteousness and Regulations, if

not Tact.

Lack of coin had meant a proliferation of paper

money based on nothing more substantial than

some-ones promise to pay, which in turn depended

on chance. For a period rum was used as currency

and the government used to settle its debts with

rum. The usual exchange was: I bottle of rum

equals Åí1. The price of tea was 40/- a pound; a large

allotment of land in the centre of Hobart cost 5

gallons of rum.

Hull went to Hobart full of zeal and tried to reorganise

affairs there. First he suggested to Lt. Gov.

Sorell that some of the oxen in the government herds

could be dispensed with and replaced by horses.

The oxen were used in all heavy works, ploughing,

road making, hauling timber, and carting stone etc.

But Sorell, beyond doubting that it was a question

that concerned the Commissariat put the issue aside

without any commitment until Commissioner Bigge

had passed comment.

Then Hull really offended the Lt Gov. by preaching

economy and morals, and questioning the custom of

supplying an issue of rum to the constabulary and

watchmen at Launceston and Hobart Town.

When Hull tried to re-organise the system of store

receipts Sorell referred the matter to Macquarie in

Sydney. The Governor, whose position in the dispute

with Drennan had been supported in London, now

backed up Sorell in his turn. Which was a good thing

for Hull, for by September 1820 Drennan’s system

was found sadly wanting by a committee of inquiry,

and he was later dismissed with a deficit of over 6,000 pounds on his books.

Hull must also have had many dealings with that

prominent citizen Edward Lord, but it does not

seem that he got tangled in any of his schemes.

Edward Lord, as well as being the owner of

thousands of acres, also owned three trading ships,

which imported goods, particularly rum, for his

warehouses at Hobart and Launceston. For years he

was the largest supplier of grain and meat to the

Commissariat, and his relations with the first two

Commissaries, Fosbrook and Hogan, were, if not

corrupt, certainly open to question and two later

Commissaries, Broughton and Moodie, accused

him of attempted bribery, At various times he was a

magistrate, and a member of the Lieut. Governor’s

court, but when Governor Arthur arrived in 1824,

he realised he had met his match and bowed out

gracefully.

It was the Commissariat’s responsibility to feed

and clothe most of the predominately convict and

military population. This meant that the colony’s

main industry was the production of grain and meat

for sale to the government store. When not enough

was produced on the government farm at New

Town, the Commissariat had to buy supplies from

private settlers. The Commissary could wield strong

influence; he could refuse to buy from people he did

not like, and was also in a position to commandeer

imports off ships.

Also, it was Hull who organised the first

comprehensive muster (or census) of all people

and stock in the colony in November 1819 and then

another in October 1820; previously only convicts

had been mustered. In those 11 months there showed

an increase of nearly 2,000 persons.

On February 21st 1820 Commissioner Bigge

arrived in Hobart to make his report on the state

of the colony, and spent three months collecting

information and statements. His final report was to

change the convict system, cause much enmity and

reveal many anomalies. Hull had left Sydney a few

days before the arrival of Bigge on Sep. 26th 1819, and

therefore had not met him personally but all people

in the colony were aware of his importance.

Sorell and Hull each presented their version of their

differences to Bigge, and although Bigge conceded

both men had done a difficult job to the best of

their ability, his final recommendation was for the

replacement of both men.

To encourage a self-supporting society Bigge hit

upon the idea of promoting the production of fine

wool to be sold on the British market. To improve

the flocks of Van Diemen’s Land Sorell sought the

help and advice of Governor Macquarie. He in turn

approached John Macarthur, who had returned to

N.S.W. following his years of exile after the Rum

Rebellion. Macarthur agreed to supply 300 rams to

V.D.L. on the understanding that he would be paid

for them in land. Consequently Macarthur received

in return 4,368 acres of the Cowpastures to add to his

already large property there.

In forwarding these 300 rams in July 1820 Macquarie

left it to Sorell to distribute them among the settlers.

More than a third of this shipment of what were in

fact Macarthur’s inferior sheep died on board the

ship “Eliza” where they were penned up for 19 days

on their way from Sydney. The surviving 185 rams

were subsequently distributed to those flock owners

whom Sorell considered most likely to apply best

attention and care to them.

George Hull was called upon to serve on the

committee for the distribution of these rams, but

when he learnt that several ex-convicts were also on

the committee he withdrew and lodged a complaint.

Governor Macquarie in N.S.W. had seen fit to allow

ex-convicts to play a part in the order of the colony

and Sorell tried to follow his example. But the

circumstances in Hobart were much different to

Sydney and Hull was not the only colonist to object.

Commissioner

Bigge also supported the colonist’s views and when

Sorell threatened to withhold any claim to a land

grant in retribution Bigge said Sorell did not have

that power and recommended that Hull should have

the usual privileges such as a land grant if he settled,

and Hull immediately forwarded a claim.

The first free settlers had been granted land

around New Town (then called Stainforth Cove)

a settlement two miles north of Hobart where the

government farm was already established. A little

further along the north bound road the small

settlement of O’Brien’s Bridge grew where the road

crossed the Humphrey’s Rivulet, and this later

became Glenorchy.

It was at O’Brien’s Bridge that Hull bought several

small farms with the intention of building up a large

estate and he chose 1,000 acres to the south-west of

his purchased land in the heavily timbered hills, with

a view to using and selling the timber, opening up

a lime kiln, and eventually using the land for sheep

pasturage.

In notifying the Lieut. Gov. of his choice, Hull

complained that there was no land available, which

could be classified as suitable for agriculture, and

indeed, so freely had land been given that Sorell

had to call a temporary halt until further outlying

districts could be opened up.

The Lieutenant Governor Sorell could do no more

than give Hull a Ticket-of-occupation, dated 1820,

by which he was permitted to occupy the land by

issuing in general terms a description of the land

he chose. When Hull had sailed from England

he carried with him a letter from the Under-

Secretary-of-State dated May 1818, communicating

Lord Bathurst’s decision leaving it to Governor

Macquarie’s option to give him a grant of land as

was customary. But before he could select his land in

N.S.W. Hull had been sent to Hobart.

So when Governor Macquarie toured V.D.L. in

April 1821 he gave authority to the Lieut. Governor

to make Hull a reserve of 2,000 acres, which was as

good as a grant, and only subject to good behavior,

until such time as Hull retired on half-pay, there

having been issued new regulations forbidding

granting land to serving military officers.

Governor Macquarie and his family had come to

V.D.L. for a farewell tour, travelling the way overland

from Hobart to Port Dalrymple (Launceston) and

thus opening up much of the countryside and

establishing a roadway that was many times later

traversed by the Hull family, By the time Macquarie

returned to Hobart Town in May, Hull had been

superseded.

In April 1821 the Treasury in London had recalled

Commissary Drennan from Sydney and replaced

him with Deputy Commissar General William

Wemyss, and at the same time sent Assistant

Commissar General Affleck Moodie to take charge

of the Commissariat Department in Hobart. As

well as Moodie being Hull’s superior, there was the

fact that Sorell had officially complained of Hull’s

attempts to “assume unwarranted powers just as

Drennan had tried to do in

Sydney”. So although there was no direct cause to

replace Hull, he was considered Drennan’s prot.g.e,

and for the time was out of favour, Hull was now

Moodie’ s assistant, and in charge of the Bond store.

As King’s Bonding Warehouse Keeper he had charge

of all spirits arriving in the colony, and some fees

were paid in spirits, which accumulated and were

used as money in purchasing some of the little farms

of which Tolosa was made up. It was also part of his

job to test the proof of the spirits, and several times

a year he had to make the journey to Launceston to

attend to the Commissariat affairs there.

Hull’s feelings were undoubtedly put out by the

changes but now he had more time to attend to other

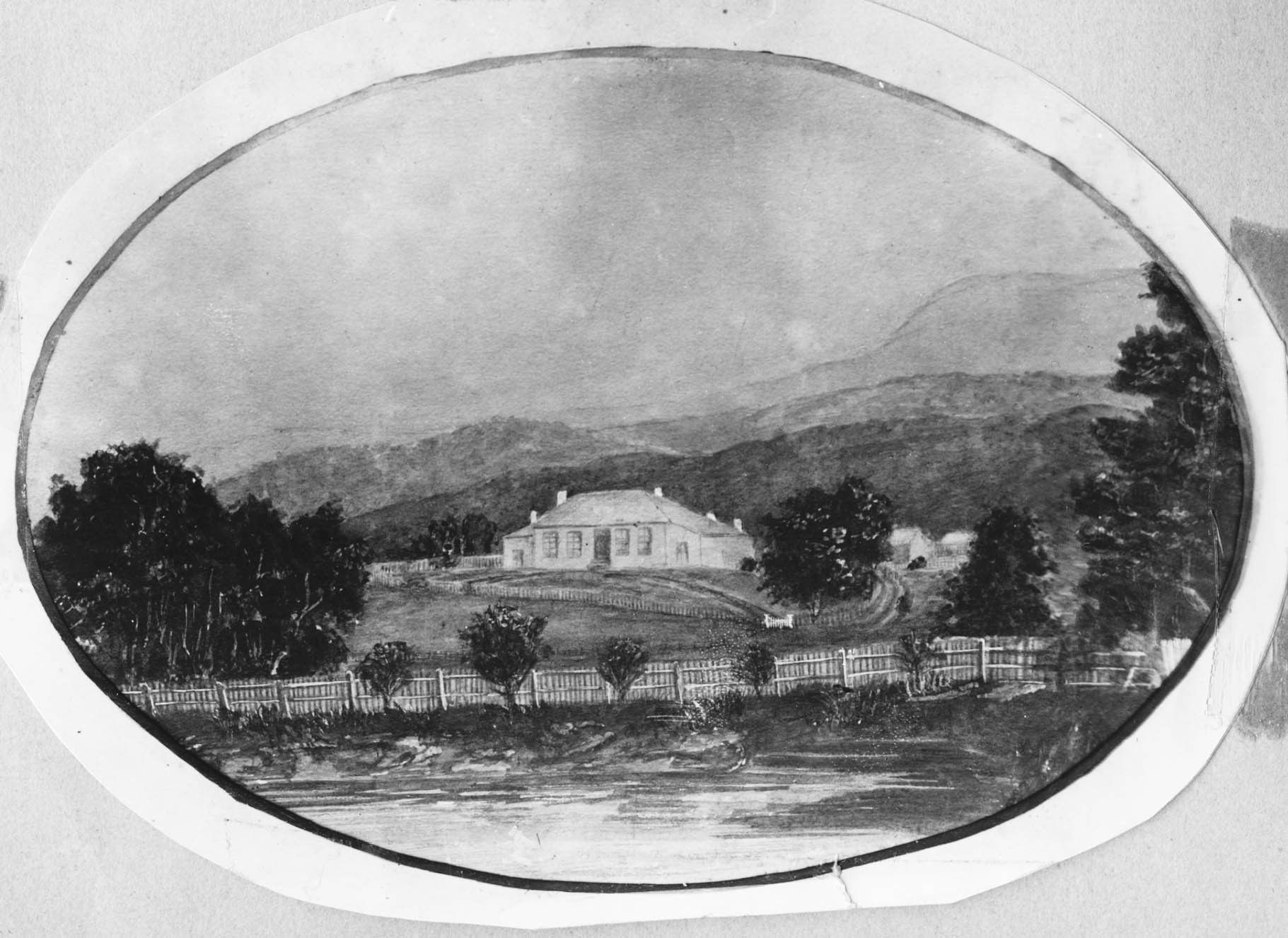

affairs. He began the building of his home “Tolosa”

on one of the small farms he had purchased,

expending upwards of 600 pounds on house and land, and

started what was to become a long protracted paper

battle for the titles to his “grant”.

The name he chose for his new home, “Tolosa”,

comes from a little village in Spain where he stayed

awhile during the Peninsular War when he was in

Wellington’s entourage. When he had started the

building his neighbor Dr Scott told him he thought

it far too large, and that he would run to ruin

building such a large house, neither men realizing

then that the family would grow to 13 children.

It was made of hand-made pinch brick, the outer

walls being triple thickness and the inside walls

being double thickness. It was undoubtedly built

by convict labour, and the lime for the mortar was

burnt on the property. It had cedar floors, doors,

shutters, and window ledges. The floorboards were

8 inches wide and great folding doors of cedar went

right across the main rooms, each 16 feet square, to

be opened when balls were held. When the house

was demolished an

offer of Åí1,000 was made for the doors alone. There

were fourteen rooms altogether, with attics in the

roof, which had windows facing the mountains, and

there was an eight feet wide passage running right

through.

The fourth child, Robert Edward, was born in June

1821, at Tolosa in the beginnings of the house. Two

years later a little daughter Harriet Jane was born in

May 1823.

'Tolosa', Glenorchy, Tasmania

But Hull had been ordered to take charge of the

Commissariat at

Launceston, as Fletcher and Roberts had been

appointed as assistants to Moodie in Hobart, so he

arranged for tenants to care for his land and home,

and once more Anna had to pack her goods and

chattels and set off into the wilderness.

In July 1823 the family moved to Launceston, with

the 5 children travelling on a mattress in the chaise

cart and with several other carts carrying luggage,

the journey of 125 miles taking 4 days.

The history of Launceston runs parallel to that

of Hobart. The northern part of the island was

settled in 1804 and deemed a separate colony of

Port Dalrymple until 1812 when it was united and

subordinate to Hobart. Governor Macquarie travelled the road between the two settlements first

in 1811 and again in April 1821, but the road was not

completed until 1822, when Lt. Governor Sorell set

chain gangs to work, and tolls were introduced to

help cover the enormous expense.

There were two settlements in the northern area

struggling for survival - Launceston on the river flats

and George Town on the headland near the sea. In

1819 John Youl was appointed the first Chaplin for

Port Dalrymple and Gov. Macquarie insisted that

he settle at George Town. However when Macquarie

returned to England in Feb 1822 commonsense

prevailed with regard to Launceston, which was

growing rapidly in spite of orders into a sizeable

township of 900 people and the Youls and others

came trooping back.

In those early days there was little communication

between Launceston and Hobart. The mail carrier

had two donkeys, one of which he rode; on the

other he strapped the mailbags. He carried a horn,

which he blew on entering a township or nearing a

farmhouse. There were no postage stamps: letters

were marked 3d or 4d in red to denote how much the

receiver had to pay before delivery. Quite a number

of escaped convicts were roaming the countryside as

bushrangers and the aboriginals were considered as

extremely wild.

In 1823 the number of houses at Launceston was

given as 11 brick and 116 wooden, with 80 other

buildings, inns, stores, government barracks and

so forth. With the exception of a few houses in

Brisbane Street, the building of the town was

confined more or less between the banks of the

North Esk River and the line of Cameron St. There

was also what used to be called the Female Factory

where women prisoners washed and mended clothes

of Government officers and such others as were

prepared to pay the government for those services.

But there was no church and Rev. Youl used a

blacksmith’s shop for his services on Sundays.

When Gov. Macquarie had visited Launceston in

May 1821 he found the original public buildings in

such a state of decay and dilapidation that he gave

orders for the immediate erection of a new gaol, a

Military barrack, a hospital, a Commissariat store

and Granary, a barrack for one Military officer, and a

barrack for an Assistant Surgeon.

In January 1824 Hull became involved in what

appears to have been Tasmania’s first “affair of

honour”. Records of the Launceston Police Court

reveal beside the name of John Smith; “Having sent

a challenge to George Hull Esq. on the 18th instant;

bound over to appear before a Bench of Magistrates

on 1st Saturday

in Feb: P. A. Mulgrave Esq.” John Batman was

charged with having conveyed the challenge. Duels

were illegal, and all men were bound to keep the

peace.

John Batman had left Sydney December 1821 to

settle at Launceston, and his first settled work was

as a supplier of meat to the Government Stores. By

1824 he had accumulated enough money to qualify

for a land grant of 500 acres, which he selected on

the timbered slopes of Ben Lomond, Batman was a

forceful character and had many influential friends.

It was in 1824 that young six-year-old Hugh was

enrolled at the Hobart Town Academy and Boarding

School which had been opened in Feb. I823, and

conducted by James Thomson from Edinburgh.

Hugh boarded at the school and only rejoined his

family at Christmas time when his father went the

125 miles there and back in the gig to collect him. A

hard time for one so young.

In August 1824 a disagreement flared up between

Hull and Richard R. Priest, the assistant Surgeon in

the colony, Hull with-held the stores and rations of

meat which were due to Priest, claiming Priest owed

a large sum of money to the Commissariat; when

Priest objected to this, Hull also threatened to withhold

his half years pay till the debt was discharged,

and eventually the matter had to be settled by appeal

to the new Lieut. Gov. Colonel Arthur.

All was not work in the busy office though.

According to a contemporary news report, King

George the Fourth’s birthday, 1825, was celebrated in

the following manner: “The members of the county

of Cornwall Club, pursuant of an Advertisement,

dined at the Launceston Hotel on Saturday last

(April 23) in honour of His Majesty’s birthday. The

Union (flag) was displayed at Fort Cameron at

Noon, a Royal Salute was fired which was followed

by a feu-de-joie

by the detachment of the 40th Regiment here;

the shipping participated in the general feeling

by hoisting a diversity of flags and firing. The

remainder of the day was spent in a manner highly

demonstrative of the loyalty and affection of the

Respectable Inhabitants of Launceston.”

But whatever the loyalty of the free citizens, the

whole island was still one gigantic gaol, and convicts

were still tempted to abscond into the bush. A

frightening outbreak of bushranging in the 1820s

was caused by a well-organised gang led by Matthew

Brady. Riding on the best stolen mounts they

moved north, raiding farms and eluding all efforts

to capture them. By the time they arrived at the

outskirts of Launceston “Brady’s Boys” had become

a public menace. They did not enter the town, but

their activities kept the nervous townsfolk in a

state of alarm. Gov. Arthur took decisive action,

and organized highly mobile groups who knew the

country well. John Batman was placed in command

of the Volunteers from Launceston, Colonel Balfour

led a detachment of the 40th Regiment, and Arthur

entered the field personally leading a group of

horsemen called “The Flying Squad”. Brady was

finally captured by Batman in April 1826, when he

was wounded and surrendered without a struggle,

but only after R.R. Priest had been killed.

The assaults of the natives, who had been

antagonised into retaliation by harsh treatment and

misunderstanding, also made journeying about the

countryside a dangerous occupation. At this time

the remote estates were guarded by soldiers, loopholes

pierced the walls, fierce dogs were stationed as

sentinels, and the whole strength of a district was

sometimes employed in pursuit of either natives or

bushrangers.

In January 1825 Gov. Arthur travelled to Launceston

and on the 25th laid the foundation stone for St

John’s Church; it was intended to be a replica of St

David’s at Hobart, but was arbitrarily reduced by

a third to suit a smaller population. It was built by

convict labour, with locally made bricks, and was

first used for Divine Service on Christmas Day 1825.

It was capable of seating 550 persons, including

the convicts seated in the two galleries along the

sides, and during the services there was a constant

interruption from the clanking of the chains by the

prisoners in the galleries above. George Hull’s sixth

child, George Thomas William Hull, was born at

Launceston and christened January 18th 1826 by

Rev. Youl in the new church three weeks after the

opening. Two other sons

Temple and Henry were born at Launceston also.

An organ was installed in the church on September

1827 in time for the dedication of the church on

March 6th 1828, but the tower was not built until

1830 (this tower is the only visible remaining part of

the original church).

In his book of Reminiscence Hugh wrote, “My

father was accustomed to play the organ in St John’s

Church on Sundays, as there was no-one able or

willing to take on the duty; and my sister and myself,

with a number of the Commissariat Clerks used to

form a very respectable choir. When my father had

taught one of the clerks to play he transferred his

duties and the Church wardens presented my father

with a purse of sovereigns”.

Governor Arthur had taken charge of the colony

on May 12th 1824, when Lieut. Gov. Sorell had been

recalled on Bigge’s recommendation owing to his

liaison with Mrs. Kent. In his zeal and insistence

that government agents should also conform to

his strict Calvinistic views, Gov. Arthur turned to

examine the conduct of civil servants and other

officers connected with the authorities and found a

staunch supporter in Hull. At the end of 1825 V.D.L.

was to become a separate colony from N.S.W. and

Arthur was to be in complete charge, answerable

to London, not to Gov. Darling in Sydney, and a

complete new system

of Public Departments had to be organized.

From the 25th September 1826, the Commissariat

Department of V.D.L. became independent of

the N.S.W. Commissariat. The hierarchy of the

commissariat remained the same, with Moodie in

charge, and on the 12th April 1828 Hull was also

appointed to the position of Assistant Treasurer at

Launceston, for 5/- per day, and it became part of his

duty to collect the quit-rents for the government and

other revenue.

The old Commissariat building where Hull had his

office (built in 1827) is now the military barracks, the

Customs House and Bonded Store now house the

Agricultural Department, It is recorded that Hull

always attended the office in full uniform, a deep

blue cloth coat, the breast covered in gold braid,

large gold epaulettes, cocked hat, and steel sword.

An official return made out 22-8-1826

at the time of take-over shows that Hull received a

pay of 9/6 per day or 149-10-0 a year.

In September, on 22nd 1827, another son was born,

Temple Pearson Barnes - the name Barnes being in

honour of his friend William Barnes who owned the

Trevallyn estate and established the first brewery in

Launceston beside the Tamar on Paterson St.

In 1828 the second son, Robert, was sent to join Hugh

at Dr. Thomson’s school. Education was a point

of status as well as an essential pre-requisite for an

acceptable job, and the Åí100 a year for the two boys

was the very limits that Hull’s wage could afford.

In1830 when it was time for Fred to start school,

Hugh was withdrawn and joined his father’s staff as

a junior volunteer clerk (as apart from the convict

clerks conscripted to work).

To Hugh these were happy years. He wrote later, “At

night the Officers used to come down to our house

from the barracks and spend their evening over the

Commissary’s grog; whilst he told us long stories of

his adventures in the war, much to the delight of us

all. I remember the bower of Roses and the Willows

in the garden, wherein he used to play the flute

and we used to sing our little songs, for we were all

musical children. Many a picnic we used to have in

those years with music and dancing and merriment,

all happiness.”

In 1829, on September 16th, another little boy was

born, Henry Jocelyn, and like all men with a large

expanding family Hull looked around for further

income. When the Postmaster died suddenly Hull

applied for his job as well but his application was

refused.

Hull had constant thoughts of retiring on half pay

and following pastoral pursuits, so on April 7th 1826

he memorialized Gov. Arthur to claim a further

1,000 acres in the wooded hills behind his farms.

Sorell’s original order for his reserve had allowed

2,000 acres, the same as most officers, of which

he had claimed half, and as no better opportunity

seemed to present itself, he decided to claim the

second portion before he lost the chance. At this

time he had 30 cows and 800 sheep to support his

claim.

Hull kept in constant touch with the tenant on

his property at Hobart, and when he heard in

September 1826 that a Mr. Simmonds was trying to

take over 500 acres and his lime kilns, all part of the

first reserve, he protested to the Colonial Secretary,

who upon investigation found that Mr. G. Evans

the surveyor had not marked the land off on the

official maps. But as Hull’s claim was well-known

Gov. Arthur supported his claim and Mr. Simmonds

withdrew.

Six months later Hull asked for an official sketch

of his land boundaries so that he could make

arrangements with the lime burner to erect a bushrailing

fence, in lieu of rent, to forestall any more

pretensions.

But 12 months later he again had to lodge a

complaint when his tenant wrote to him that a Mr.

Walton was taking off two loads of wood a day from

Hull’s reserve near the Lime Kilns. Upon inquiry it

was found Walton had permission to cut wood on

Emmett’s land adjoining Hull’s and he was given a

warning to keep within the boundaries.

Gov. Arthur was tired of all the confusion that

surrounded questions of land rights and in 1828 he

set up a Land Board and appointed commissioners

to survey and valuate all lands, and to set up a

system whereby public lands could be leased by

auction. All reserves were to be abolished, so

Hull applied to the Governor to have his reserve

acknowledged as a grant. Gov. Arthur felt bound to

point out that Macquarie’s orders of 1820 forbade

issuing grants to military officers still serving the

government, but at the same time he felt he was

obliged to honour Sorell’s promise made when

the reserve was issued, so he compromised his

conscience by back-dating the grant to 8th May 1824

(when Sorell was still in power). Grants were in fact

far from free as the quit-rents asked in most cases

were equal over the years to the purchase price.

In September 1830 Hull, like all military personal,

was engaged in the government “muster” of all

aborigines on the island. In an official letter he wrote:

“When it was necessary to arm all the inhabitants

of the country to check the assassinations by the

Aboriginal natives, Colonel Arthur led the whole

disposable convict population against them in

military array, though necessarily without all that

organisation adopted in the army. Every soldier in

the colony was employed in the same duty, so that

the military and treasury chests were left unguarded

-, those in my charge at Launceston containing

some thousands of pounds in British coin had been

always kept in a weather-boarded building, and my

servants, clerks, and storemen were convicts, and yet

no disorder or robbery occurred. When the “Black

War” as it was called, was terminated, every convict

delivered up his arms and quietly returned to his

former avocation.”

In 1831 Hull had completed 20 years service as an

officer in the army, and suffering ill health as well

as growing deafness (due to cannon blasts in the

Penninsular War) he retired in March on half-pay

of Åí90 a year, and bade farewell to his friends at

Launceston. He left a town greatly changed from

when he had first arrived, with a population, which

had nearly trebled in the past 8 years.

RETURN TO HOBART

The return journey was a weary one. There were

now eight children, some of them in the gig, some

in the chaise-cart, some on the bullock cart. They

were four days travelling, and arrived late at night

at Tolosa, weary and bad-tempered. The house was

in bad repair in the hands of a drunken tenant,

and Hull immediately put in an application for

convict servants, and was granted 21, to help put

the place back into order and back into production,

The assignment of convicts was an essential part

of the convict system, but only to gentlemen

who could give them a good example to reform.

Prisoners were fed and clothed by the settlers, but

were not supposed to be paid or offered any other

inducements.

Their first winter at Hobart was very severe, the

ground being covered with snow for some days

together, and the children made a snowball that

lasted a fortnight. Hull and his three eldest sons had

to work hard all day cutting down trees and bushes,

which they heaped into large piles and set fire to

them at night. There were no fences around the

paddocks and the pigs and cows had to be herded

every night. Hull proposed to turn his sword into

a pruning hook, and not figuratively speaking, but

actually did so. He was often to be seen cutting and

slashing the willow bushes with his sword in a most

masterly manner. In the next few years he spent

about 1000 pounds in the erection of extra lime kilns and

cottages, clearing land, and putting in about a mile

of fencing.

Only a few weeks after their return a third little

daughter was born, to be called Anna Munro after

her mother.

They found Hobart Town to be much altered and

grown since they had left it eight years previous.

Lieut. Gov. Arthur’s influence was to be seen in all

directions. Essential community features had been

established in the shape of roads, mail and banking

services and religious and educational facilities.

Arthur preferred military men as government

servants and he had dismissed men who had shown

an independent spirit. Affleck Moodie was still in

charge of the commissariat and had built himself

a spacious home at Battery Point. New Town was

becoming a pleasant suburb, with brick and stone

houses in large gardens surrounded by sweet briar

and hawthorn. The pioneering atmosphere had

changed for one of prosperity; it was an area of

peace and restfulness where wives met for chatter

about the inadequacies of domestic servants, whilst

husbands commuted on horseback to city offices and

warehouses.

Upon Offering his retirement Hull applied to the

Secretary of State for a grant of land, in March l832,

to mark his 20 years service, and was looking for

something like 1-2,000 acres such as Yoeland, Boyes

and Roberts had received being his fellow officers.

He was most disappointed on receiving a reply from

the Colonial Secretary when he was only granted

560 acres. The Col. Sec. took into account the 2,000

acres he already held, but Hull considered that as

being separate, as a grant for settling in the colony.

The figure of 2,560 acres was established by Lord

Bathurst in 1825 as the maximum for settlers without

capital, those settlers with capital being expected to

buy land. This third allotment Hull also took among

the wooded hills north of Humphrey Rivulet; at the

end or Chapel street.

In 1834 a new Board Of Inquiry for the Commission

of Land Titles was established to settle locations of

grants. Hull sent in all relevant letters and details,

and his claim was recognised by general description,

but as it had never been surveyed, and the problems

presented to the surveyors were so great, his

application for the deeds was put to the bottom of

the pile.

The Commissioners had a large number of problems

and disputes to unravel as much of the conveyancing

had been done without legal advice or documents

of any kind. On 15th December 1835 Hull wrote a

letter to protest strongly against a claim on a farm he

had bought from Captain Blythe, which was being

claimed by the original grantee who had sold it to

Blythe. Hull’s protest was upheld and he was given

the titles to the 120 acres after I4 years possession.

For a while upon their return to Hobart the family

attended their old church, St David’s in Hobart, but

moves had already been instigated by Gov. Arthur

towards the establishment of a new church to be

built in conjunction with the new King’s Orphanage

at New Town. Arthur was not entirely disinterested

in making the proposal since the new proposed

Government House was within the area, which

would be served by the church.

On 6th January 1854 Gov Arthur laid the foundation

stone, and it was opened for worship on 20th

December 1835. The original seating consisted of

high box pews in the centre of the church arranged

in collegiate fashion facing a central alleyway.

There were two galleries, that on the south facing

the entrance accommodated the convicts and their

guards and was furnished with narrow backless

benches with a division to separate male and female

prisoners; the north gallery was intended for the

orphans, but gradually as the church became more

and more fashionable and so well attended the

orphans were ousted and rented pews installed.

Beneath this gallery were seats raised 3 steps above

the floor level for servants and those who did

not rent pews. Pew rents were handed over to the

government and they in turn paid for all labour and

repair work on buildings, mostly by convict labour.

The clergymen were also paid by the government.

Hull insisted that because of his position he had

the right to sit in the Lieutenant Governor’s pew

in his absence. This was in answer to the church

authorities writing that he did not have that right.

The vergers also objected to Hull’s habit of allowing

various other people to sit in his pew, when they

had paid no rent. Hull refused to pay his rent for

12 months and was summonsed by the church

authorities, but be must have capitulated because he

was always considered a member of the church.

For most of the ensuing years the family walked to

church, nearly two miles across country around the

brow of the hill until they joined the Main Road to

cross the bridge over New Town Rivulet. Although

Hull naturally had several carthorses for farm work,

he never kept a carriage, and the chaise was crowded

with 3 persons and unsuitable for his large family

to travel together to church. On many Sundays a

church service was held in their own home, with

Hull reading the service, attended by the children,

servants, visitors, and sometimes neighbours.

By 1830 Gov. Arthur’s attitude had begun to make

him many enemies. Arthur saw V.D.L. only as a gaol

for the punishment and reformation of criminals;

his self-imposed role as the improver of mankind

exposed him to the hatred of many convicts and

also stirred the wrath of free settlers who wanted to

secure their land and claimed their British rights to

settle their own affairs with an elected legislature.

There were many unpopular court cases concerning

free settlers as opposed to Arthur’s very arbitrary

authority. A government decree in June 11th 1831

stated that all land from that date was to be sold at a minimum price of 5/- per acre. The new settlers

objected claiming they had been promised free

grants, but Gov. Arthur was relieved to be free of the

duty of issuing grants which seemed to cause more

discontent than gratitude.

Another decree, issued in May 1832, caused a storm

of protest among the settlers already established.

Arthur informed all landholders that government

proposed to collect all arrears of quitrent. Petitions

were signed all around the country claiming it would

be unequal, unjust and intolerable. Its collection,

they said, would in one fell swoop absorb the labour

of years. Payment of quitrent would involve in ruin

the prosperity and happiness of every landholder

in the country. Quit-rents had been imposed in

November 1823 and confirmed in Nov. 1824. All

persons receiving grants of land were to be free of

quitrent for the first seven years. After that time

quitrent of 5% per annum on the estimated value

of the land was to be paid. In the redemption of

his quitrent the grantee was to have credit for one/

fifth part of the sums he might have saved the

government by the employment and maintenance of

convicts.

At the same time it was found that the wording of all

grants was illegal, and they had to be re-submitted.

Many mistakes and frauds were discovered and

many disgruntled landholders were encouraged to

consider the idea that both revenue and expenditure

should be in the hands of those who paid the taxes.

Hull seems to have remained silent on issues where

he could not support Governor Arthur, preferring

not to censure a man he so respected.

The year 1832 also marked a great achievement in

Hull’s personal career. Gov. Arthur, who knew Hull

had the qualities he required of men who served

him, placed his name on the roll of the Justices of

the Peace in a List published in the “Hobart Town

Gazette” on July 27th 1832. ‘The jurisdiction of the

Lt. Gov. ‘s court was purely civil, and only extended

to pleas where the sum at issue did not exceed Åí50;

but no appeal lay from its decision. All causes for

a higher amount and all criminal offences beyond

the cognizance of the Bench of Magistrates were put

before the Supreme Court and Chief Justice Pedder.

The popular movement, which started with

land-rights and moved on to a bid for an elective

legislature now turned to the problems of

transportation. But this was one area where Hull,

and a number of other landowners who looked for

cheap labour, found they were in agreement with

Arthur. Arthur dashed off thousands of words to

the Secretary Of State to prove that transportation

was the best secondary punishment ever invented by

mankind. To address and convince a wider public

of his personal views on the subject he composed a

pamphlet entitled “Observations upon Secondary

Punishment”, had it printed in Hobart Town, and

sent copies off to London to join in the debate in

England.

On October 1836 Gov. Arthur was recalled and

temporarily handed over to Lieut.-Colonel

Snodgrass. In his unusually long term as Governor

the population had increased to 40,000, the revenue

from ÅíI7,000 to Åí106,000, the exports from Åí14,500

to Åí320,000, the colonial vessels from I to 17, and

the churches from 4 to 18. He received praise for his

efforts from London, and from his supporters in

V. D. L., and on Saturday 29th October, 500 people

assembled at Government House to bid farewell. He

walked with Chief Justice Pedder down Murray St

to the New Wharf followed by all the public officers

and military, and several hundred town’s people, and

embarked on the “Elphinstone” amid cheers and a

salute from the ships in harbor.

The new Lieut. Governor who took up duty in

January 1837 was the renowned explorer Sir John

Franklin, a man who carried his culture and his

civilisation with him. Almost the antithesis of Col.

Arthur, Franklin considered his duties as Gaol

Commander peripheral to his main pre-occupation

which was developing scientific research within the

colony.

A census paper filled in on December 31st 1837 shows

that Hull still had 7 male and 4 female assigned

convicts on his estate, the family was still growing,

and the farm developing. Georgina, his eldest child,

was married in the June to Phillip Emmett, and

therefore does not show on this census.

In September Hull got a medical certificate to prove

that he was fit for full time employment, and for

a time from Oct 11, I837 acted as assistant to the

Director General of Roads and Bridges, Captain

Cheyne. Hull was to superintend the correspondence

and the stores and implements required for use in

the Department, and received 300 poundsper annum.

He had asked Assistant-Commissary-General

Moodie to consider his application for full time

employment in the Commissariat and when

Moodie suddenly died 27-11-1838 Hull petitioned

the Governor for Moodie’ s position, pointing out

that he was the most senior officer available, but

D.A.C.G. Roberts returned from sick-leave and

accepted the Advancement.

The Roads and Bridges Department was reorganized

late in 1838 and Cheyne was designated Director Of

the Department of Works, and Hull resigned from

the position as his assistant. It had not been a very

happy relationship and developed into a feud that

carried on several years until Cheyne was dismissed

in 1841.

On March 23rd 1839, in response to an advertisement

in the Gazette, George Hull submitted a tender to

supply unslaked lime to the government in the name

of his son Fred, with himself named as bondsman,

at 6+3/16 pence an imperial bushel. This was in fact

the only tender put forward, but it was not accepted,

Cheyne maintaining that the quality or Hull’s lime

was uneven, and he re-advertised for tenders and

asked Mr Price to put in a quote. Hull objected to

this snub, and listed the various buildings around

Hobart where his lime had been used, principally

the Queen’s Orphan School, St John’s Church,

Trinity Church, the penitentiary wall, and the

Custom’s House foundations. After much bickering

Cheyne allowed Hull to have the contract being sure

to write in the terms “to supply lime as required”

and then found excuses not to use Hull’s lime as it

was not required. Hull and Cheyne were still feuding

until the end of 1841 when Montagu, the Colonial

Secretary, who also had a great personal dislike of

Cheyne, pressed for Cheyne’s dismissal.

In December 1838 a new Caveat Board under

chairman W. T. Champ was established to finalise all

claims to grants of land. Once again Hull was asked

to forward all papers and certificates concerning his

original grant of 2,000 acres, so that a title could be

drawn up, and a public advertisement had to be put

in the newspapers 26-7-I839 describing the land that

was claimed in his name, just in case anyone else also

had a claim to that land, the early maps had been

so haphazard. In 1834 it had been accepted on the

description of Mr Frankland, the Surveyor General,

and Hull thought this was sufficient “as the land was

too rough for Surveyors to go through”, The titles

were finally drawn up on 8-7-1840 but Hull objected

to some of the charges the Commissioners claimed

against him and the titles were not passed over until

the matter was settled in 1841.

Lady Jane Franklin, like her husband, also believed

in advancing the culture of the people. In 1839 she

bought 54 acres of land in Lenah Valley from George

Hull at from 1 to 3 pounds per acre, to be used as a site

for a botanical garden and a museum. In March

1842 Sir John Franklin laid the foundation stone of

a new Greek Temple - a natural history museum

with simple pediment columned in brown stone,

which was called Acanthe. Ronald C. Gunn turned

from office duties with the Convict Department to

managing Acanthe for Lady Jane and editing the

Tasmanian Journal of Natural Science.

The philanthropic mood also caught Hull, who

gave land for St Matthew’s Presbyterian Church at

the corner of Tolosa St and Main Rd. It is a small

but excellent example of Romanesque Revival

architecture designed by convict architect James

Blackburn. The foundation stone was laid by Sir

John Franklin on December 20th 1839 and dedicated

two years later. Years later one of the family gave the

family bible to the church, but they first removed the

family history entries.

In 1840 the world traveller and mountain explorer

Count Strezlecki visited Van Diemen’s Land. Three

miles north of Mount Wellington, in the county

of Buckingham is a lofty mountain attaining the

altitude of 2,300 feet above sea level; this mount

is covered with timber and was named Mount

Hull by Strezlecki after George Hull as Hull’s land

encompassed the slopes and lower hills.

The year 1841 also brought great sadness to the

family, for shortly after the last and thirteenth baby

was born, their third son Robert contracted T.B. and

died aged 20 years. Consumption as it was generally

known then, was very prevalent, and incurable, and

was no respecter of class or age.

The 1840s was an era that was rich in cultural

activities, unsettled with political agitation for

the abolition of transportation, prosperous in

trade revenue, yet depressed local prices had a

serious effect on employment. After a period or

speculation in stock and land payments to bank

and other finance companies fell due; cattle bought

at 6 guineas a head sold at 7/6; sheep were sold at

6d per head. Bankruptcy became widespread and

unemployment and distress common.

The situation in Tasmania was worsened by the

release of prisoners who had completed their

probation to compete for employment. Every

branch of business was affected and there was a

great falling off in many industries. By now Hull had

four sons working as clerks in various Government

Departments, but finances were getting harder and

harder. For the previous decade he had been buying

small lots of land to add to his farm, now he was

forced to release them.

On 19-5-1843 Hull inserted an advertisement in the

Mercury offering Tolosa for lease.

‘TOLOSA’ : - To Let or lease for 7-10 or more years

and entered upon immediately, the House and

Estate of Tolosa, 4. miles from Hobart Town,

together with the lime kilns and sub-tenancies. This

Estate contains about 2,000 acres of land and affords

an excellent run for a small flock of sheep and is

well adapted from its vicinity to market for a dairy.

About 70 acres are in crop and preparatory thereto

and a considerable additional quantity may at once

be ploughed up. The rent will be very moderate to

a respectable tenant and further particulars may be

known on application to P. G. Emmet.”

Hull evidently did not get a favorable response for

the following year, in February 1844 he mortgaged

1,600 acres to the Commercial Bank to secure a loan

of 500 pounds.

1844 was also a year of change within the family.

Fred was married in February, Jane married Fred

Downing in June, and in October Hugh was married.

George Hull was 58 years old, a grandfather of 4, and

considered too old for Government employment

except for the position he held as Justice of the Peace.

In 1839, after seven years in a mainly honorary

position, Hull was fulfilling the duties of sitting

magistrate on minor cases at Glenorchy. Colonel

Arthur had divided the island into Police Districts

with a stipendiary magistrate for each, but J.Ps still

had a roll to fill.

In 1841 Hull memorialized the Governor suggesting

that he might be appointed visiting magistrate with

the purpose of dealing with the misdemeanors of

the men in the road gangs, naturally with a slight

remuneration to cover costs, to ease the burden of

the overworked Police Magistrate, but his suggestion

was not followed up.

In l859 there were 325 names on the Commission of

the Peace in Tasmania, and twenty years later when

he died, Hull’s name was fifth on the roll, his seniors

being Capt. Malcom Laing Smith, Sir Robert Officer,

Captain Dumeresq and Mr Thomas Mason. He

always considered “Muster Master Mason” a friend

and colleague, but never gained that gentleman’s

notoriety, possibly because although stern, he was

never harsh with those under him. He brought

his children up with a compassion for the lower

orders of mankind such as convicts, emancipists,

and aborigines, while teaching them their duty in

upholding the class of free settlers.

His sons were later to tell their children of the hours

they spent being drilled in social etiquette, standing

behind a chair and moving it out with just the right

amount of deference for a lady to sit upon, etc.

In February 1848, by which time Hull had repaid 450 pounds of the loan from the bank, he again approached

the bank for a further loan and arrangements were

made for the sum of 917 pounds. The property was made

over to the Commercial Bank, and the Bank was

to be permitted to lease the land, or part of it, and

receive all income from the lease. The lease of the

tenant, Lodder, was effective for ten years

from 1st March 1847, and remained in force after Hull

repaid the loan, but the lease payments were then

payable to Hull. During this time the family retained

the use of the home and the surrounding orchard on

the original purchased blocks.

Hull’s name appears many times in the record books

as being involved in land transactions. On 3-8-I854

he sold his grant of 560 acres to Fred Downing, his

son-in-law, with another 100 acres. On 10-8-1848

he sold a block to James Aitken who left it to his

daughter Nettie (Hugh Hull’s wife) who in turn left

it to her two sons Herman and Hugh, who held it

many years. The Glen Lynden farm, established on

a block in Chapel St was let and leased many times

and other blocks re-appear several times as they were

leased. Well-known names such as W. Dixon, W.

Crowther, R. Grant, T. Grove and Henry Buckland

show as having leased the big block of 2,000 acres on

which Hull often raised ready cash.

From now on Hull led a life of a country squire,

although without the comfort of an adequate

income.

In August1843 Sir John Franklin was replaced by

Sir Eardly Wilmot, and in January 1847 Sir William

Denison took over the leadership. Hugh was clerk in

Sir William’s office and counseled his father to write

a long memorial on the benefits of transportation

in the reformation of convicts, in support of views

put forward by Denison. Hull, of course, had only to

recall the arguments put forward by

Colonel Arthur, and in October 1851 presented a very

lengthy treatise on the subject. But in the end the

Anti-Transportation League won, and landholders

such as Hull had to manage without assigned

servants.

After the depression of the 1840s, the gold strikes at

California in 1849 and on the mainland in 1850 gave a

most welcome boost to trade and money once more

circulated freely. The farmers and landholders were

given good prices for their produce and Hull could

redeem the land he had mortgaged, November 1850.

Three sons, Fred, George, and Temple, and a

daughter Georgina who had married Philip Emmett

went to Victoria in search of gold and settled there to

start a new life.

Hobart had been growing and changing all the time

but one change that particularly interested Hull was

the building of the new museum an 1861 on what

had been the site of his first home in Tasmania. The

little seedlings be had planted that first December

were now fine big gums that had to be lopped so that

they did not interfere with the building.

The little settlement of O’Brien’s Bridge had grown

populous and independent of New Town, and in

1864 was declared the Municipality of Glenorchy.

George Hull and his old friend William Fletcher

were appointed as auditors to the new council and

his son John Hull was appointed the first Council

Clerk.

Cooley’s horse-drawn buses provided an hourly

service between Albert Rd and central Hobart, a

great boon for a family that did not keep a carriage,

although up to his 80th birthday Hull could, and

sometimes did, walk into Town, a distance of nearly

5 miles.

Most of the estate was now divided into small

farmlets and let to tenants. Hull took great pride

in his fairly extensive orchard, he cropped about 50

acres, kept an old horse and cart, and relied on local

men for seasonal work.

The house was big and old and rambling, and several

members of the family tried the idea of moving back

in with their parents to care for them in their old

age but George was too independent. Whenever he

or Anna were ill, or in need of a change, they went

to Jane and her family at Battery Point, where they

always received a sympathetic welcome.

Anna died at Tolosa on 28th January I877, after a

lingering illness and was buried at the New Town

cemetery.

George stayed most of the time after that with

Jane, troubled by bouts of dysentery and an awful

dizziness as a legacy of his service in Spain. He died

on Tuesday, June 24, 1879, at the advanced age of

93, and was buried in the church-yard adjacent to St

John’s Church, New Town.

In George’s will he left instructions that Tolosa and

its farms were to be sold and the money divided in

5 parts - one part to each of the four daughters and

the fifth part to be divided between the six surviving

sons.

It was all sold in 1880 according to the will and the

new owner of the house had a verandah built across

the front with a lot of iron lacework. Verandahs did

not become fashionable in Tasmania until the 1870s

because the summers there are not as severe as in

N.S.W. A new driveway was put in from the street

which was lined with fir trees, and it branched both

ways around a circle before reaching the house. The

Owens family lived there some time.

In 1950 Tolosa was put up for public auction by a Mr

Pitt, the owner at that time, and it fetched 5,400 pounds but

by then there were only a few acres of land with the

house.

The man who demolished the house in 1968,

Mr Molineaux, died two years later and his wife

maintained that Tolosa killed him, as he insisted on

doing the whole job of wrecking alone.

The land was all subdivided and incorporated in the

suburb of Glenorchy, and the only reminder left now

is a street called TOLOSA ST, which used to lead up

to the old house. A block of two-story flats is on the

site of the old home.