And so begins the Australian branch of the

Jeanneret family...

After practising in London till 1828, Dr Henry

Jeanneret applied for a post in Australia and was

recommended for a land grant in proportion to his

capital under the “Land Regulations Act of 1827”.

Reluctant to sell out before certain that the colonial

climate would suit him, he was assured at the Colonial

Office that he could visit Sydney and reserve land

while he returned to England to sell his property.

Confirmation of these negotiations was given by Sir

George Murray in 1828.

With a letter of introduction from Sir Richard Dundas

to Governor Arthur, he departed England on the brig “Tranmere” with the intention of setting up

practice in either Sydney or Hobart Town. He arrived in Van Diemans Land on 12th. November 1829

from where he proceeded to Sydney, arriving in December 1829.

Dr Henry Jeanneret

L.S.A., M.D., L.R.C.S

1802 - 1886

Dr. Henry Jeanneret was born on 31 December 1802 in the Poultry, St Mary Colechurch, London, England. He died on 12

June 1886 in Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, England. He married Harriet Merrett, daughter of William

Merrett and Elizabeth Beard on 15 December 1832 in St. James Church, Sydney, New South Wales,

Australia. She was born about 1809 in England. She died in June 1873 in Romsey, Wiltshire, England.

He then married Frances Ann Barnett, daughter of William Barnett and Ann Matthews in 1874 in

Great Malvern, Worcestershire, England. She was born on 23 August 1826 in Princes Risborough,

Buckinghamshire, England. She died on 02 November 1901 in Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, England.

Henry Jeanneret and Harriet Merrett had the following children:

1. Charles Edward Jeanneret was born on 09 February 1834 in New South Wales, Or Hobart

Australia. He died on 23 August 1898 in Wyrallah, Richmond River, New South Wales, Australia.

He married Julia Anne Bellingham, daughter of Francis Bellingham and Julia Rowe Ive on 12

June 1857 in St Phillips Church, Sydney, New South Wales. She was born on 14 June 1837 in

Gracechurch, London, England. She died in 1919 in Hunters Hill, New South Wales, Australia.

2. Frances Charlotte Jeanneret was born in 1837 in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. She died

in 1837 in on voyage to Hobart, Tasmania.

3. Jane Warren Jeanneret was born in 1838 in Port Arthur, Tasmania, Australia. She died on 03

October 1857 in Leicestershire, England.

4. Henry James Jeanneret was born in 1842 in Haider, Ireland. He died on 30 August 1860 in Wee

Waa, New South Wales, Australia.

5. Francis Crosbie Jeanneret was born on 06 June 1847 in Flinders Is., Tasmania, Australia. He died

on 05 March 1873 in Poole, Dorset, England.

6. Sarah Charlotte Jeanneret was born on 01 November 1848 in Launceston, Tasmania, Australia.

She married Thomas Chambers on 10 January 1889 in Parish Church Ryde, he was born in 1829.

He died on 24 August 1896 in Summer Hill, Ashfield, New South Wales, Australia.

7. John Louis Jeanneret was born on 26 November 1850 in St. Mary, Islington, Middlesex, England.

He died on 05 January 1877 in Hunters Hill, New South Wales, Australia.

1802 - Born in England 31st December

1802

1817 - Apprenticed to the surgeon John Symmonds, City of Oxford for 5 years.

14 March, 1817

c.1822 - Studied medicine at The Radcliffe Infirmary (Oxford); worked as a Dresser at The London

Hospital and at the City Dispensary, London

1823 - Studied at the University of Paris

1824 - After studying at Oxford, London and Paris graduated from University of Edinburgh, 7

October 1824. Elected as a Licentiate of Society of Apothecaries

1825 - Moved to Edinburgh. Active both in clinical medicine and in natural history. He was

elected President of the Plinian Natural History Society of Edinburgh University; awarded

the Doctorate of Medicine (Edinburgh University) and elected as a Licentiate of the Royal

College of Surgeons

1826 - Negotiated to emigrate to Australia to take up land under “Land Regulations of 1827”

Confirmed by Sir George Murray

1828 - Letter of introduction provided by Sir Richard Dundas to Governor Arthur

1829 - Emigrated to Sydney, N.S.W. and set up Medical practice

1831-1832 - Treatise and Lectures on Dentistry, by Henry Jeanneret M.D. published. Article by

contributor and his first Australian Book of Dentistry

Practiced for some years in Colony (N.S.W.) chiefly in capacity of Dentist

1832 - Married Harriett Merritt of Sydney

Notice of intention of leaving Sydney for Van Diemans Land appeared in the Australian

Newspaper

1834 - Son Charles Edward born Sydney 9 May 1834

1834 - Dr. Jeanneret opened a Medical Practice at 31 Murray Street, Hobart Town and practiced till

the end of 1837

1835 Claim for Land by Dr. Jeanneret

1837 - Daughter Frances Charlotte born

1837 Infant daughter Frances Charlotte died on voyage from Sydney

1838 - Relinquishing his Medical Practice in Hobart Town, Dr. Jeanneret received appointment in

Service of Crown of Medical and Spiritual Charge of Point Puer, Port Arthur

Daughter Jane Warren born

1840 - Daughter Charlotte Sarah born

1842 Posted to Aboriginal Settlement on Flinders Island as Surgeon, Commandant and Justice of

the Peace

1842 - Son Henry James born

1843 - Suspended from office by Governor Sir John Franklin

1844 - Resumed practice at 31 Murray Street, Hobart from 21 September

1844 - Son Francis Crosbie born

1845 - Presumed to have spent some time at the penal settlement at Norfolk Island

1846 - Reinstated to Flinders Island by the British Government

Son John Louis born

1847 - Settlement at Flinders Island disbanded

1848 - Dr Jeanneret and family left Flinders Island aboard the “John Bull” and arrived at

Launceston 18 February 1848

1849 - In a published statement in the Colonial Times 27 February 1849 through a Secretary of

States Despatch, the British Government ordered the Colony to renumerate Dr Jeanneret to

the sum of one thousand pounds in settlement of his claims

1850 - Dr Jeanneret and family sail for Sydney aboard the ‘William’ on 11 April 1850

1851 - Returned to England with family and took up residence at 12 Finchley Road, St Johns

Wood, 18 August 1851.

1851 - Dr Jeanneret had printed in pamphlet form a letter to the Rt. Hon. Earl Gray - being a short

explanatory appeal relative to the authors conduct as Superintendent of Flinders Island.

1854 - Pamphlet published by Dr Jeanneret after Cholera epidemic in London

1874 - Wife Harriet died

1874 - 13 November, married Frances Ann Barnett, eldest daughter of Mr William Barnett at the

Abbey Church, Great Malvern, Worcestershire, England

1886 - After returning to England, Dr Jeanneret died at Cheltenham 16 June 1886.

On arriving in Sydney, he applied for a reserve grant but was told that he must take out a bond for

five hundred pounds to remain in the colony for three years. Protesting against this condition he

established a practice as a surgeon and dentist. It was during this time that Dr Jeanneret wrote the

first book on dentistry in Sydney, ‘Hints for the Preservation of Teeth’ (1830).

Dr Jeanneret had a very keen sense of preventive medicine and particularly of the prevention

of dental ill health. He publicly advocated, in his book, general rules for the preservation of the

teeth. He advocated daily brushing of the teeth and gave practical illustrations in lay terms how a

toothbrush might be used. He advocated a dentifrice of charcoal mixed with chalk and powdered

cinnamon. He advocated that a silken thread might be used for flossing the teeth. Chapters in

his book dealt with Teething, Shedding of Teeth, General Rules for the Preservation of the Teeth,

Diseases, Decay, Toothache Remedies, Diseases of the Gums and the subject of Artificial Teeth and

Palates.

During those first five years in New South Wales Dr Jeanneret took a great interest in everything

tending towards the advancement of the colony. He was a strong advocate of the establishment of

Schools of Art and his lectures on scientific subjects helped to develop the resources of the colony.

In 1831 he was active in dysentery epidemic.

On the 11th December 1832 he married Harriet Merrit of Sydney, sister of the wife of the late Mr

Francis Mitchell. They were married at St James’s Church. Their first son, Charles Edward was born

on the 9th May, 1834.

Not enjoying the climate due to ‘being by day eaten

up by flies and by night by mosquitoes’, Dr Jeanneret

requested a transfer to Van Diemans Land. He gave

notice of his intention to leave Sydney for Van Diemans

Land in the following notice which appeared in The

Australian Newspaper 8th November 1832:

Dr Jeanneret begs to inform friends and

public that he proposes leaving NSW

shortly and requests those requiring

his assistance as a dentist to make

early application having been obliged to

disappoint many persons on leaving for

Van Diemans Land.Clarence St, Sydney,

New South Wales 8th October 1832.

It was not until 1834 that Dr Jeanneret and family

sailed from Sydney for Hobart Town. On arrival he

established a medical practice at 31 Murray Street,

Hobart Town where he practiced until the end of 1837.

1835 saw the start of a long winded attempt by Dr Jeanneret to obtain land which he understood,

before leaving England, would be made available upon application.

He duly lodged an application with the NSW Government on 24th March 1835 which was evidenced

in a note from Sir George Murray to General Darling and an enclosed memo from Mr Ferguson. A

number of communications concerning Dr Jeanneret’s land claim were made between Secretary of

State Spring Rice, Sir George Murray, General Darling and Lord Glenelg , but were of no avail.

A letter from Government House dated 27th October 1835 stated that “Dr Jeanneret appears to

labour under a misconception in supposing that there was an intention to except him from the

operation of any established rules. No record of any instruction to that effect having been transmitted

to General Darling.” On the 25th January 1836 the claim was dismissed in a terse letter from

Government House with the words: “This department unable to trace any application on papers

authorising same.”

The following year, 1837, Dr Jeanneret’s wife Harriet gave birth to a daughter Frances Charlotte

Elizabeth in Sydney. Two months and eleven days after her birth, on the return voyage from Sydney

to Hobart Town, Frances died. Her tombstone is set in a wall at St Davids Park, Hobart.

In 1838 Dr Jeanneret relinquished his medical practice in Hobart Town to take up an appointment in

Service of the Crown as Medical and Spiritual Charge of Point Puer, Port Arthur. The settlement at

Point Puer was a prison where many hundreds of boys aged from eight to twenty years old, who had

been transported from Great Britain, were kept. Dr Jeanneret did much to alleviate the hardships

that the boys endured. The system of securing the juvenile prisoners to a triangle and flogging with

the cat’o’nine tails in the presence of all their comrades was deeply opposed by Dr Jeanneret and

eventually abolished during his tenure at Point Puer. Apparently, during his time at Point Puer,

Dr Jeanneret fell foul with Captain Charles O’Hara Booth which was to prove detrimental for him

in his later appointments. Having incurred the displeasure of the authorities by his leniency, Dr

Jeanneret was forced to abandon his charge and returned to medical practice in Hobart Town where

he practiced until 1842.

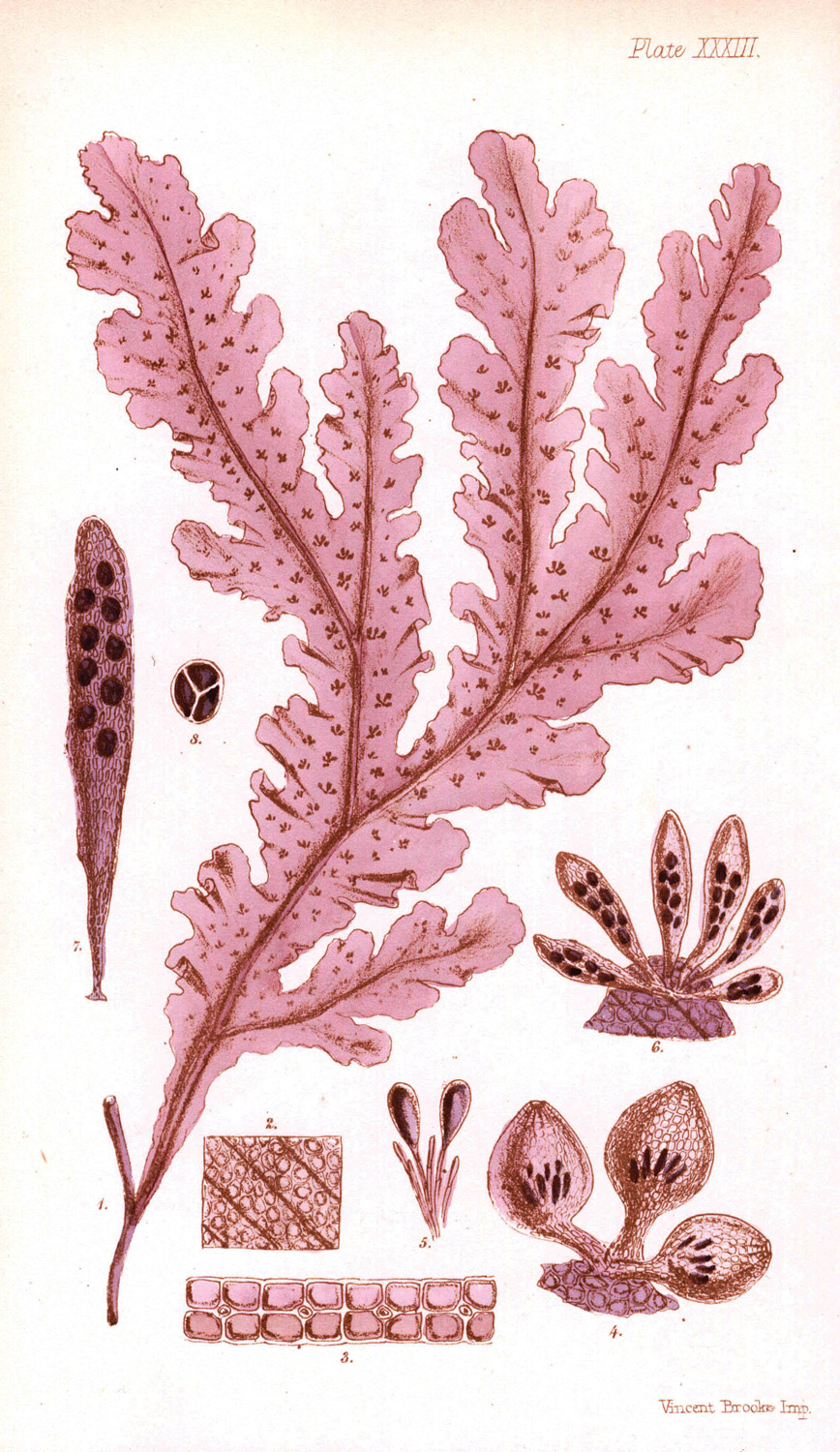

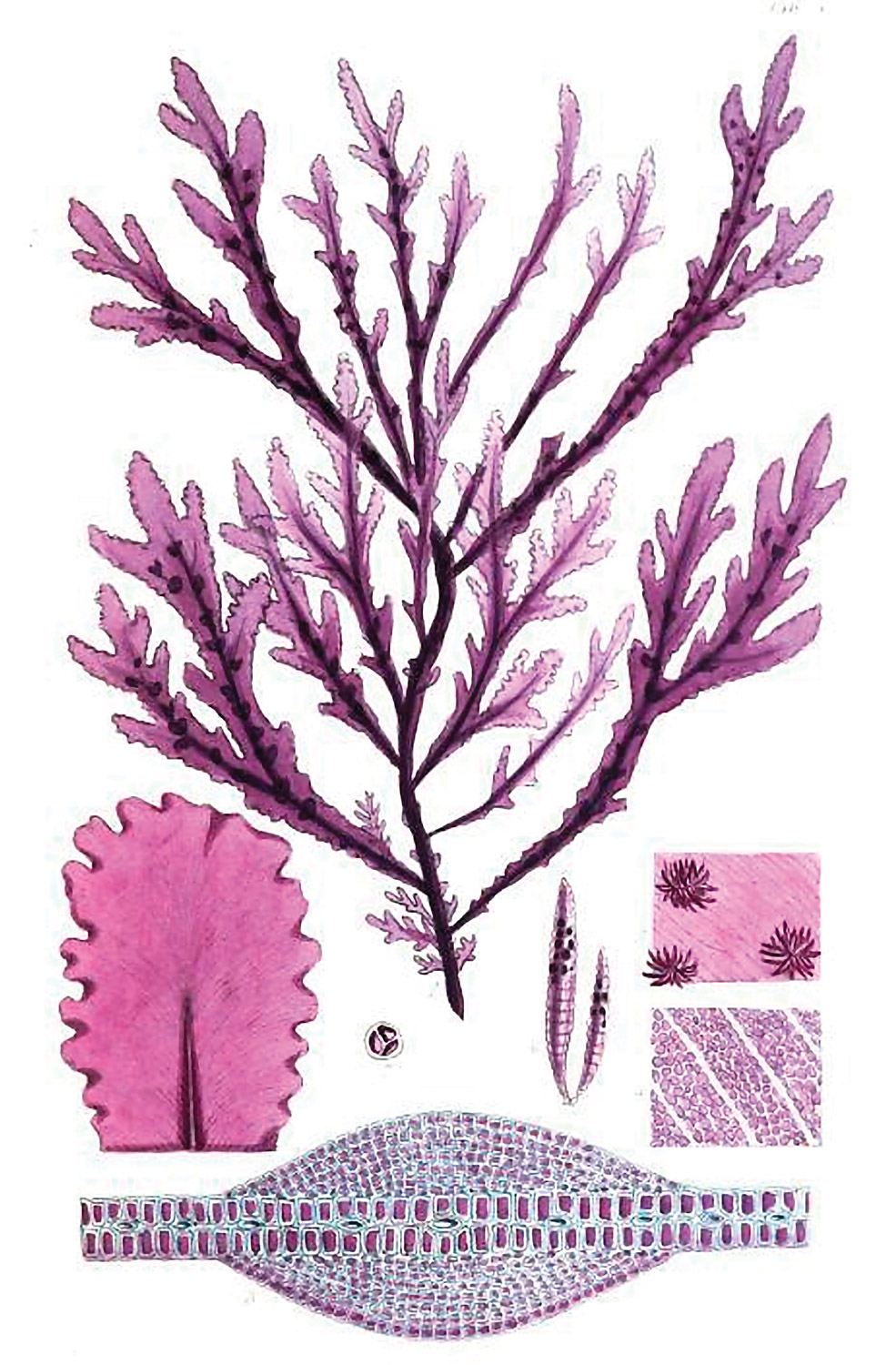

Jeanneret’s clinical skills as a surgeon and dentist, together with the bureaucratic controversies in

which he was eternally embroiled, have overshadowed his work as a botanist. He was interested

in botany generally, but particularly in seaweeds and other marine plants. He corresponded with

two of the great doctor botanists of his era, Professor William Henry Harvey, Keeper of the Dublin

Herbarium and subsequently with botanists in both England and Scotland. He sent specimens of

marine algae from Port Arthur to Dr Hooker in London and the new genus Jeannerettia was named,

in 1847,

“in dedication ... to Dr Jeanneret of Tasmania, from whom we have received a number

of interesting algae, gathered at Port Arthur, and among them the first specimens we

have seen of this new remarkable plant ”. Jeanneret’s name is well known in the world Y 33

of botany . His eternal memorial is the name of the beautiful red cold water algae,

Jeannerettia pedicellata and Jeannerettia lobata. These delicate red seaweeds, with their

glowing colours, are common in the seaborne drift of the southern shores of Australia.

There is a drawing of the type specimen, sent from Port Arthur in Tasmania by Dr Henry

Jeanneret in 1838. Drawn by another doctor-botanist, Dr William Henry Harvey, it

features in Harvey’s “Nereis Australia”, published in 1847, with acknowledgments.”

Plates of Jeannerettia from Harvey’s “Nereis Australia”

Given the displeasure of the authorities at Jeanneret’s performance at Point Puer it is curious that

in 1842 he was appointed to the Aborigine Settlement “Wybalena” on Flinders Island as Protector

of Aborigines, Surgeon and Commandant and Justice of the Peace, by the hand of Governor Sir

John Franklin . Perhaps it was Jeanneret’s reputation as “... a brilliant medical officer who had a vast

knowledge of the treatment of dysentery ” that motivated this appointment at a time when Aboriginal

mortality at Flinders Island was high.

Regardless of the reasons for his appointment, he was to take charge at “Wybalena” at a very low

point in the history of the demise of the Tasmanian Aboriginal people. According to Bonwick, the

historian,

“After departure of Robinson from Flinders Island and his failure to have Natives

transferred to Port Phillip the aborigines sank into an apathy from which they never

emerged.”

Of the two hundred natives originally relocated to the Settlement on Flinders Island, there were only

fifty two surviving when Jeanneret took up command of the Settlement. These consisted of twelve

married couples, eleven single men, six single women and eleven children in various stages of ill

health.

On arrival at Wybalena, Dr. Jeanneret was much shocked at the Islands affairs. He found the rations

inadequate for his charge and even tampered with by the small military party still esteemed necessary

for the safety of the Settlement.

Bonwick also wrote of Jeanneret

“Of an impulsive, energetic nature and highly sensitive in his conscientiousness he was

led from the rebuke of wrong doing to active denunciation and was early involved in

personal collision with the soldiers whom he accused of malpractices with the Natives.

Engaging in voluminous correspondence with the Government, the officials long tired

of the Native question and never appreciating the pertinacious exhibition of abuses

preferred to get rid of the difficulty by the suspension of the Superintendent in 1844 .”

According to Lyndall Ryan in her book “The Aboriginal Tasmanians”, the Aborigines were

indifferent to Jeanneret’s position and his difficulties increased when two unexpected groups

of Aborigines arrived - one from Port Phillip, the other from Cape Grim. They were to have a

profound effect upon the establishment. Jeanneret’s problems were further compounded by Clark,

the catechist who has been described by Plomley as anarchistic and whose interference was mindless

and destructive with a meaningless determination to cause trouble.

Dr Jeanneret had determined to make the Aborigines self sufficient by allocating them plots of

land for growing vegetables as well as flocks of sheep. He introduced a system of rewards for those

that were prepared to work. Payment was made for work performed and profits from the sale of

vegetables and wool were distributed accordingly. Typically the money earned was used to purchase

treats such as tobacco, sugar and clothing. The group of Aborigines from Port Phillip undermined

this system, believing that they should not have to work for such extras.

It is difficult to rationalise the varied reports of Dr Jeanneret during his appointment to Flinders

Island. On the one hand he received support from people like Dr Nixon, Bishop of Tasmania and

Lady Jane Franklin, whilst on the other he was dammed by the political leaders of the day. Many

historians seem supportive of his actions and dismiss the many petty quarrels with which he was

embroiled. Certainly Dr Jeanneret appears to have been a tenacious opponent who did not know

when to leave well enough alone. Perhaps some of the cruelest comments encountered by this writer

are those found in an annotation by Governor Denison to a volume of papers concerning dealings

with Dr Jeanneret in the archives of the Colonial Secretary -

“The whole thing is a tissue of absurdity from end to end. If Dr Jeanneret had his deserts

he would be whipped like an unruly schoolboy, and his whelp of a son as well...”

Obviously tempers were frayed over the issue of the Tasmanian Aborigines which proved to be a

massive blunder and disgrace to the Tasmanian Government. It should be noted that an emissary

from the Government, Matthew Curling Friend, spent three weeks at the settlement investigating

claims against Dr Jeanneret. Friend had previously been a member of two boards of enquiry into

affairs at the settlement. Without going into the details of Friends findings, Plomley writes

“The minutes of the evidence taken by Friend contain many statements in favour of

Jeanneret - and none supporting Clark which can be held to be unbiased - but so much

black had been applied to Jeanneret’s image that any application of a different colour

could not stick.”

Dr Jeanneret’s whelp of a son, Charles Edward, in later years (1885) was described in the book

“Australian Men of Mark ”

“As a public spirited and enterprising citizen, and Alderman both of his own suburb and

of the City Council, and later as a member of the Legislative Assembly, he is in many

worthy respects an acknowledged representative man.”

On the 21st November 1843 Dr Jeanneret was dismissed. He returned to Hobart Town to plead his

case and also resumed his medical practice at 31 Murray Street, Hobart Town from September 1844

until he was reinstated at Flinders Island on the 18th February 1846.

Three weeks after Jeanneret’s dismissal Sir John Franklin accompanied by Lady Franklin, Dr. Nixon

- Bishop of Tasmania and several officials visited Flinders Island on the 12th December 1843. The

party minutely inspected the establishment. It appears that the visit only lasted one day as evidenced

by a letter from Lady Franklin to Mrs Jeanneret dated the following day 13th December from aboard

the “Flying Fish”.

“Dear Mrs Jeanneret,

We shall remember our visit to you with much interest and pleasure and I beg you to

accept my earnest wishes for your improved health and strength and for your future

welfare. With kind compliments to Dr. Jeanneret.

Believe me dear Mrs Jeanneret.

Very truly yours,

Jane Franklin.”

On his return to Hobart, Dr Jeanneret harassed the Government seeking reasons for his dismissal

and the vindication of his character. failing to receive either satisfactory replies or pecuniary

compensation, he petitioned the Secretary of State in February 1845 for reinstatement and

compensation. These were granted by Lord Stanley in a despatch dated 11th August 1845, who

directed that:

“immediate measures be made to compensate Dr Jeanneret, either by restoring him to the

office he has lost, with all arrears of salary; or by placing him in some other equally lucrative position

with the payment of those arrears”.

The soldiers on the island were withdrawn and Dr. Jeanneret was granted full control. His triumph

over the local authorities did not lessen the spleen of his enemies nor silence the voice of calumny and

reproach.

To quote Plomley once again,

“...there is much to be said in favour of him, however strongly he acted as ‘the boss’ in his

dealings with both the whites and the blacks. Jeanneret’s job was a difficult one. He had

to contend with Franklin’s stinginess on the one hand, and with an intractable problem

of management of the Aborigines on the other. And opposed to him were not only the

Governor and the administration in Hobart, but also Robert Clark and the Aborigines,

the latter stirred up against him by Clark and as well wanting to get as much as possible

for nothing and annoyed that they had to do something to earn their luxuries, even if that

something were very little indeed.”

Early in 1846, Jeanneret received a letter of congratulations from his friend Dr. Nixon, Bishop of

Tasmania.

2nd. January 1846.

Congratulations on your reappointment, Testimony of gratification.

Signed F.R. Tasmania

In April of the same year he received another letter of encouragement from the Bishop

7th. April 1846

Expressing satisfaction of safe arrival at Flinders Island and satisfactory arrangements of

withdrawal of soldiers.

Signed F.R. Tasmania

To quote the historian, Bonwick, support for Dr Jeanneret may be found in the words of Dr Nixon,

‘who was ever a friend to both’.

“Yet knowing him well and honouring him much I am sure he misrepresented himself, for of all

men I know few with more real kindness of nature, or more profound regard for his duty to God.

For his pious and gentle Lady the Natives cherished tender feelings.”

All was not well though, almost immediately upon his return to Flinders Island a petition against

him was got up upon the apparent inspiration of Dr M.J. Milligan with the clerical assistance of

Clark the Catechist purporting to be from “the free aboriginal people” of Van Diemans Land - dated

17th. February 1846 and signed by eight of the Natives. The petitioners claimed that Dr. Jeanneret

carried pistols in his pockets and threatened to shoot them, also his pigs ate the natives food and

that the natives were inadequately clothed.

A number of curious documents bearing on this matter are preserved in the Tasmanian Archives

most of them chiefly remarkable for their faked simplicities of style .

The poor men afterwards repudiated their own act and attributed it to bad counsel.

Dr Jeanneret replied to the petition with a long rebuttal on 12th June 1846. It has been noted that

his response was ‘as could be expected from someone obsessed with the injustice to himself ’.

Lieutenant Friend was appointed to investigate and reported on his questioning of the natives, that

they reported the statements had been made for them.

Inflexible in Justice the Doctor needed suavity to soothe. Earnest in the discovery of a wrong,

he may have lacked the judicious prudence which refuses to see everything, or which perceives

extenuating and ameliorating circumstances. His very integrity dissociated him from the

sympathies of his subordinates and the rigidity of his righteous rule perhaps increased the

restlessness and discontent of his little state.

The battle with Clark, who was in truth the author of the petition, raged on until the opportunity

arose for Jeanneret to stand him down from his duties.

“The Catechist, Clark, was accused of cruel treatment and neglect of the children under his care

and they were therefore removed from under his roof and the officer was suspended from service.

Mr. Clark did not deny his having flogged the girls but declared he had done it in religious anger at

their moral offences. One in particular had been seduced into improper society and was very long

kept in rigid seclusion”.

The tragedy of the situation according to Plomley was that:

“What is so very evident is the extent to which the Aborigines were used in this war, which was

really one between Clark and Jeanneret, with the government a willing recipient of anything to

Jeanneret’s disadvantage.”

“In a letter answering some enquiries of mine (Bonwick) about the blacks, Dr. Jeanneret wrote in

bitterness of his disappointment on 10th. March 1847. The official directions of the Government

provide amply for their handsome provision, though hitherto a faction has often interfered with the

instruction furnished. I think so far from being neglected, they are and have been plagued by too

much interference”.

It was a month after that date of that letter that the following communication was addressed to Dr.

Jeanneret.

“His excellency has it in contemplation to break up the Aboriginal Establishment at

Flinders Island at an early period and that should his intention be carried into effect

your appointment as Superintendent would probably cease as your services would not be

required.

No charges are here made and no reference is made to mal-administration. On the

following day a letter was sent intimating the appointment of a successor Dr. Milligan for

the express purpose of effecting the removal of the Aborigines to the mainland.

As this is to be accomplished without unnecessary delay Mr. Milligan’s arrival will take

place on or about the first proximo, when you will have the goodness to hand over your

charge to that gentleman and be prepared to return to Van Diemans Land by the same

vessel which conveys him to the settlement.”

The Aboriginal settlement at “Wybalena” Flinders Island was abandoned late 1847 by order of

Governor Sir William Denison. Dr. Milligan having been appointed as successor to Dr. Jeanneret

for the express purpose of the removal of the Aborigines to the mainland at Oyster Cove in

D’Entrecasteaux Channel.

Dr. Jeanneret was virtually the last Superintendent of Flinders Island. He remained to see the

embarkation of the Natives under his successor Dr. Milligan all bound for Oyster Cove. At the time

of transfer according to Fenton there were forty four natives at Flinders Island.

A report in the Hobart Town Courier reports their arrival on the 20th October 1847:

“Arrived in schooners Sisters and Gill from Flinders Island with Dr.

Milligan and lady, twenty two females, fifteen aborigines and ten children

which they landed at Oyster Cove in D’Entrecasteaux Channel.”

Some time after the removal of the natives Dr. Jeanneret and family left Flinders Island in the ‘John

Bull’ arriving in Launceston February 1848. Two years later, 1850, they sailed for Sydney, New South

Wales where Dr Jeanneret continued to practice medicine. He also continued to write and carry on

his appeals to authorities claiming injustices.

In 1851, having returned to England, Dr Jeanneret had printed in pamphlet form a letter to ‘Rt.

Hon. Earl Grey - being a short explanatory appeal relative to the authors conduct as Superintendent

of Flinders Island’.

In a memorial dated 18th February 1853, Henry Jeanneret petitioned His Grace the Duke of

Newcastle a Secretary for State for the Colonies for compensation and losses and injury through

neglect of the Colonial Office. The pamphlet was entitled ‘The vindication of a Colonial Magistrate

from the aspersions of His Grace the Duke of Newcastle’.

In another dated 1854: ‘Remonstrance and

Exposure of a Colonial Conspiracy whereby

Her Majesty the Queen has been imposed

upon in a petition against Henry Jeanneret

M.D. Charges reputed: Statements by the

Duke of Newcastle were in opposition

to those of Lord Derby when Secretary

of State and the arrival of his Graces

immediate predecessor Sir John Pakington.

Dr. Jeanneret’s pamphlet “Petition to the

Queen” and resulting correspondence clearly

states his case of oppression and unfounded

accusations.

The year 1854 brought the Cholera epidemic

that raged in London and there is evidence

that Jeanneret still practiced and published a

pamphlet in French: ‘De la guerison prompte

et facile du cholera asiatique par la method

de Henry Jeanneret’ This also reveals that

cases treated included members of his

own family, his wife Harriett, a son Francis

Crosbie and a daughter Jane Warren. He

also refers to cases treated while he was in

Tasmania and his discovery of the treatment.

Harriet died early in 1874 and Henry

remarried at the end of the same year

to Frances Ann Barnett, daughter of Mr

William Barnett at Abbey Church, Great Malvern, Worcestershire, Frances Ann and Henry Jeanneret

at England on the 13th November, Cheltenham, England.

The Cheltenham Examiner of the 23rd June 1886 records death of Dr Henry Jeanneret L.S.A. M.D.

L.R.C.S. at Cheltenham England 17th June 1886, aged 84.

Probate was granted to his widow Frances Anne Jeanneret.